- Home

- J. M. Barrie

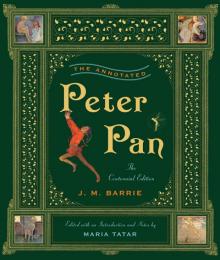

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books) Page 3

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books) Read online

Page 3

Frank Gillett’s illustrations from the 1905–6 production of Peter Pan. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

The nineteenth century invented the adventure story for children. There is not just Treasure Island, Coral Island, and Kidnapped, but also Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Adventures of Pinocchio, and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. In serial fashion, one episode after another in these works provides the repetitive delights of peril, conflict, and return to safety. In Neverland, we have the same unending cycle, with constant conflict among redskins, pirates, beasts, and lost boys. Neverland, like Wonderland, is both psychic space and social space, with external conflicts often mirroring or refracting psychological processes.

Barrie’s phantasmagoric adventures are more distinctly theatrical than those in earlier volumes for children. At times, the different camps suspend hostilities and simply parade around the island, in a kind of ceremonial display of their costumes. “The lost boys were out looking for Peter, the pirates were out looking for the lost boys, the redskins were out looking for the pirates, and the beasts were out looking for the redskins. They were going round and round the island, but they did not meet because all were going at the same rate.” The boys form a “gallant band,” “gay and debonair,” as they dance and whistle while circling the island. “Let us pretend to lie here among the sugar-cane and watch them as they steal by in single file,” the narrator writes, and proceeds to enumerate for us the dramatis personae of the play (in the double sense of the term) that will unfold before us. Peter and Wendy is filled with such theatrical moments, and it creates a spectacle dominated by masquerade, mimicry, disguise, performance, role playing, and masks. Theater was Barrie’s game, as much as fiction.

In the ceremonial march around the island, each lost boy, pirate, redskin, and beast engages in what the noted cultural historian Johan Huizinga famously described as the essence of play: “making an image of something different, something more beautiful, or more sublime, or more dangerous than what he usually is.”5 Using “imagination” in the root sense of the term, the characters create new identities in that secret, sacred space known as Neverland. There they inhabit a zone where play rules supreme. Cut off from ordinary reality, they possess a certain freedom yet are also subject to the tensions and rules found in all games and activities that we characterize as play. That kind of play, more than the cultural work of adults in the real world, can create a space of orderly form and aesthetic beauty. When we describe play, we often draw terms from an aesthetic register that seeks to capture the beauty of its movements: poise, harmony, concentration, focus, balance, tension, contrast, and resolution. Players fall under the spell of the game, and spectators are often enchanted or captivated by the performance.

Neverland is a theater for the imagination, providing the lost boys with an opportunity to have endless adventures and “ecstasies innumerable.” It is a space of beauty and imagination, but it seems at first to be a site of disorder rather than aesthetic order. Here is its description as the Darling children approach it:

Neverland is always more or less an island, with astonishing splashes of color here and there, and coral reefs, and rakish-looking craft in the offing, and savages and lonely lairs, and gnomes who are mostly tailors, and caves through which a river runs, and princes with six older brothers, and a hut fast going to decay, and one very small old lady with a hooked nose.

This first inventory gives us the mythical and mysterious in all its complicated splendors. In the heterogeneous enumeration of everyday objects that follows this passage, we begin to understand that Neverland is no utopia or garden of earthly delights—nor is it a dystopic domain of horror. Instead it forms a kind of heterotopia that mirrors the real world even as it stands apart from it, creating a new order:

It would be an easy map if that were all; but there is also first day at school, religion, fathers, the round pond, needlework, murders, hangings, verbs that take the dative, chocolate pudding day, getting into braces, say ninety-nine, threepence for pulling out your tooth yourself, and so on; and either these are part of the island or they are another map showing through, and it is all rather confusing, especially as nothing will stand still.

Neverland is presented in all its glorious variety—liberated from the tyranny of adult efforts (like those of Mrs. Darling, who “puts things straight” every night in the minds of her three children) to produce order. It gives us a higher order in which what looks like clutter and messiness turns out to have real imaginative content. Here, everything is touched by the wand of poetry, transforming itself into something new in the context of Neverland. By suspending the “real” laws of existence and of any interest at all in use-value or profit, Neverland gives us a symbolic order of true beauty with the added enchantments of play.

Historians have argued forcefully that the harsh disciplinary culture surrounding childhood finally yielded, in the eighteenth century, to opportunities for play and entertainment. Games, toys, and books were especially designed for children, and harsh childrearing practices gave way to more permissive modes and to expressive affection. Yet Victorian and Edwardian England were also known for their cruel economic exploitation of children. Small and agile, children were sent into coal mines and factories, and, most visibly, operated as chimney sweeps. At age ten, Charles Dickens famously had to leave school and work at Warren’s Black Warehouse, pasting labels onto bottles of shoe polish.

Children entered the labor force at a very young age and often worked over ten hours a day in wretched conditions. They roamed the streets of London as beggars, street urchins, and prostitutes. But if the reign of Queen Victoria witnessed the Industrial Revolution and the rise of urban poverty, it also ushered in a new commitment to education, with a dramatic increase in the number of children attending schools and with a stronger personal and social investment in them. What had once been the worst of times for children was gradually becoming, through legislative attention, a better time, particularly in the years after 1860, when Barrie was growing up in Kirriemuir, the son of a manual laborer.

With the benefit of a first-rate education provided by a father wholeheartedly committed to educating his children, J. M. Barrie never experienced the harsh social practices of everyday life. He bemoaned the loss of the pastoral in the new industrial landscape and wrote poignantly about how it had slipped away before his boyhood eyes. But childhood remained a sacred preserve for the delights of the world that he and his contemporaries had lost. Children—“gay and innocent and heartless,” as we learn at the end of Peter and Wendy—become the last refuge of beauty, purity, and pleasure. “Trailing clouds of glory,” as Wordsworth had put it, they are the source of our collective salvation.

PETER PAN: BETWIXT AND BETWEEN

Peter Pan creates a true contact zone for young and old. In fact it is his story, as staged in the play Peter Pan and as told in Peter and Wendy, that helped break down the long-standing barrier—in literary terms—between adult and child. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, with its enigmatic characters, allusive density, playful language, and sparkling wit, had already gone far in that direction, uniting children and adults in the pleasures of the reading experience. Earlier children’s books, seeking to teach and preach, had not been designed to draw adults in. Even John Newbery’s landmark A Little Pretty Pocket-Book (1744), which recognized the importance of “sport” and “play” in children’s books, was not written to delight adults. And parents may have read James Janeway’s lugubrious A Token for Children (1671) with their children—it dominated the children’s book market for decades—but the unnatural rhetoric in the effusive declarations of faith by children on their deathbeds very quickly wore thin, and it is hard to imagine repeated readings of that gloomy volume.

Fairy tales and adventure stories, which flourished in the nineteenth century, reoriented children’s literature in the direction of delight rather than instruction, and both literary forms inspired the narrative sorcery o

f Peter Pan. Drawing readers into exotic regions and magical elsewheres, they promised excitement and revelation where there had once been instruction and edification. The expansive energy of Peter and Wendy is not easy to define, but it has something to do with the book’s power to inspire faith in the aesthetic, cognitive, and emotional gains of imaginative play. As sensation seekers, children delight in the novel’s playful possibilities and its exploration of what it means to be on your own. In Neverland, they move past a sense of giddy disorientation to explore how children cope when they are transplanted from the nursery into a world of conflict, desire, pathos, and horror. Adults may not be able to land on that island, but they have the chance to go back vicariously and to repair their own damaged sense of wonder.

Barrie’s refusal to serve as adult authority (manifested in his unwillingness to recall ever writing the play and in his attribution of the work to other children and to a nursemaid) paradoxically reveals just how determined he was to break with tradition and to write a story that appeared to be by someone whose allegiances were to childhood. In a book on Peter Pan, Jacqueline Rose famously proclaimed the “impossibility” of children’s literature, claiming that fiction “for” children constructs a world in which “the adult always comes first (author, maker, giver) and the child comes after (reader, product, receiver).”6 Basing her observations chiefly on J. M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy, she concludes that authors of children’s fiction use the child in the book to take in, dupe, and seduce the child outside the book. She is particularly incensed by the narrator of Peter and Wendy, who refuses to identify himself clearly as child or adult: “The narrator veers in and out of the story as servant, author and child.”7 Undermining the very idea of authority and authorship, Barrie dared to disturb the notion of a strict divide between adult and child.

To be sure, much of what Rose has to say rings true, and, when we read about J. M. Barrie entertaining children in Kensington Gardens with his St. Bernard named Porthos, we cannot help but have the sneaking suspicion that children’s fiction may indeed be “something of a soliciting, a chase, or even a seduction.”8 But it is equally true that Barrie’s addiction to youth—his infatuation with its games and pleasures—enabled him to write something that, for the first time, truly was for children even as it appealed to adult sensibilities. And beyond that, Barrie turned a category that was once “impossible” (for Rose there is nothing but adult agency in children’s literature) into a genre that opened up possibilities, suggesting that adults and children could together inhabit a zone where all experience the pleasures of a story, even if in different ways. Old-fashioned yet also postmodern before his time, Barrie overturned hierarchies boldly and playfully, enabling adults and children to share the reading experience in ways that few writers before him had made possible.

We do not know exactly what books constituted leisure reading for children in Barrie’s day, although we have many autobiographies with detailed accounts of encounters with books ranging from the Arabian Nights (Barrie was disappointed that those nights turned out to be a time of day) to Mary Martha Sherwood’s The History of the Fairchild Family. They may have picked up one of the many English translations of the German Struwwelpeter (in which Pauline goes up in flames for playing with matches), encountered the dull pieties of books like Goody Two-Shoes (whose heroine always shows “good sense” and “good conscience”), or immersed themselves in Ballantyne’s Coral Island (a favorite of Barrie’s). What we do know is that, in the waning days of the Victorian era, adults took an unprecedented interest in reading to and writing for children. Robert Louis Stevenson developed the idea for Treasure Island when he created a map of the island with his stepson Lloyd Osbourne. Kenneth Grahame wrote parts of The Wind in the Willows in the form of letters to his son, Alastair. And, later, A. A. Milne immortalized his son, Christopher Robin, in Winnie-the-Pooh.

With the rise of compulsory education and a newfound interest in a literate citizenry, parents and writers were at long last taking the trouble to puzzle out what it would take to recruit children as eager, enthusiastic readers. Unsurprisingly, writers absorbed in childhood and devoted to children were the ones best able to fashion high-wattage stories that would enable children to sit still and listen or read.

Like Lewis Carroll, who developed and refined his storytelling skills by conarrating (telling stories with children rather than to them), Barrie did not just sit at his desk and compose adventures. He spent time with young boys—above all, the five he adopted—playing cricket, fishing, staging pirate games, and, most important, improvising tales. Here is a description of the collaborative process from The Little White Bird, with the narrator describing how he and David coauthor stories:

I ought to mention here that the following is our way with a story: First, I tell it to him, and then he tells it to me, the understanding being that it is quite a different story; and then I retell it with his additions, and so we go on until no one could say whether it is more his story or mine. In this story of Peter Pan, for instance, the bald narrative and most of the moral reflections are mine, though not all, for this boy can be a stern moralist, but the interesting bits about the ways and customs of babies in the bird-stage are mostly reminiscences of David’s, recalled by pressing his hands to his temples and thinking hard.9

J. M. Barrie’s 1906 acrostic alphabet poem for Michael Llewelyn Davies. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

In an interview, Barrie put a slightly different spin on the writing of Peter Pan, explaining his role as storyteller to the boys as well as their way of accepting the deeds described as the gospel truth:

It’s funny . . . that the real Peter Pan—I called him that—is off to the war now. He grew tired of the stories I told him, and his younger brother became interested. It was such fun telling those two about themselves. I would say: “Then you came along and killed the pirate” and they would accept every word as the truth. That’s how Peter Pan came to be written. It is made up of only a few stories I told them.10

J. M. Barrie with Michael Llewelyn Davies, circa 1912. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Perhaps, then, the fantasy of collaborative storytelling is a fiction, yet Barrie, more than any other author of children’s books, attempted to level distinctions between adult and child, as well as to dismantle the opposition between creator and consumer (the hierarchical relationship that Jacqueline Rose finds so troubling in children’s literature). He aimed to produce a story that would be sophisticated and playful, adult-friendly as well as child-friendly. At long last, here was a cultural story that would bridge the still vast literary divide between adults and children. Like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Peter and Wendy could be a shared literary experience, drawing two audiences together that had long been segregated into separate domains.

“If you believe,” Peter shouts, “clap your hands; don’t let Tink die.” In urging suspension of disbelief, Peter not only exhorts readers young and old to have faith in fairies (and fiction) but also urges them to join hands as they enter a story world in a visceral, almost kinetic manner. Whether entering Neverland for the first time or returning to it, we clap for Tink and, before long, begin to breathe the very air of the island as we read the words describing it.

When Dorothy Ann Blank, an assistant in the story department at Walt Disney Studios, was asked in 1938 to review and report on the source material for the planned cinematic adaptation of Peter Pan, she was surprised to find that the book was less transparent and straightforward than she had imagined. “I am trying to formulate a straight, simple story line,” she complained, “but it’s all over the place right now.” The plot of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens was a real challenge for her to summarize, and even Peter and Wendy had a plotline that was irritatingly difficult to capture. “It’s a swell story,” Blank observed, “but Mr. Barrie has scattered it around and made it as confusing as possible.”11

Why this sense of disorientati

on? It is not just the terrors and enchantments of Neverland that create vertiginous moments. J. M. Barrie’s narrator—with his frequent direct address of the reader (for example, “If you ask your mother”)—may create a sense of cozy intimacy, but he is also forever flirting with readers without revealing an identity of his own. Shifting rapidly and with ease from the register of an adult narrator to that of a child, he seems sometimes to be a grown-up (“We too have been there [Neverland]; we can still hear the sound of the surf, though we shall land no more”) and sometimes a child (“Which of these adventures shall we choose? The best way will be to toss for it”).

Barrie’s narrator uses sophisticated adult diction, but he is also playful, capricious, and partisan in ways that third-person narrators rarely are. In place of omniscience, we have only partial knowledge. “Now I understand what had hitherto puzzled me,” he reports at one point, as if he were writing and experiencing at the same time. “Some like Peter best and some like Wendy best, but I like [Mrs. Darling] best,” he declares elsewhere, only to denounce his favorite later as someone he positively detests. What are we to make of someone who is as fickle as the character about whom he writes? Is the strategy there to remind us about the degree to which the narrator wants to be the boy who will not grow up? In many ways, J. M. Barrie was forever straddling lines—betwixt and between in real life and as a narrator in his fictions.

THE MYTH OF PETER PAN

With Peter Pan, the boy who would not grow up, J. M. Barrie drew on both life and literature to do something massive and mysterious. He invented a new myth, one set in his own time and place—London at the turn of the twentieth century—yet also situated in another world, the made-up island of Neverland. Barrie borrowed much from literary forebears, creating a story that is not so much original as syncretic, uniting disparate, often contradictory bits and pieces from his own experience and from the foundational stories of Western culture. Philip Pullman, author of the trilogy His Dark Materials, was asked once what sort of daemon he would choose for himself (in his universe every human has an animal soulmate). His reply: “a magpie or a jackdaw . . . one of those birds that steals bright things.”12 It was Barrie’s genius to use that same skill, what the anthropologists call bricolage, making resourceful use of materials close at hand to construct a new myth.

Peter Pan

Peter Pan Peter and Wendy

Peter and Wendy Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens Tommy and Grizel

Tommy and Grizel Sentimental Tommy

Sentimental Tommy When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life

When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens

The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens The Little Minister

The Little Minister Peter Pan (peter pan)

Peter Pan (peter pan) Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)