- Home

- J. M. Barrie

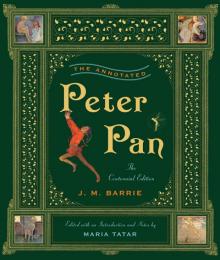

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books) Page 2

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books) Read online

Page 2

The Beinecke Library at Yale University is a six-story rectangular building with walls made of translucent marble that protect the books from direct light but transmit some light into the tower of book stacks. Its sunken courtyard contains three sculptures representing time (a pyramid), the sun (a circle), and chance (a cube). When I entered the ground-level reading room for the first time, I could not help but feel those geometric shapes resonate with my anxieties and hopes about the Barrie papers. How could I possibly read, review, and reflect on everything in the Barrie archive, even with a ten-hour working day? Although the reading room had large glass panels, it felt sepulchral, with nothing to look at but the sun-dappled concrete of the courtyard. I would have to pin my hopes on chance—the possibility that proximity to the papers would produce an intimacy and understanding deeper than what I had found in Barrie’s writings and in books about him.

One of the first boxes I opened contained Barrie’s notebooks, handwritten in a scrawl that was frustratingly illegible. With effort, I was able to get most of the words making up each sentence or phrase, but one key word always resisted decoding, and each sentence was thereby doomed to remain a mystery (or at least unquotable), drawing me into a suffocating vortex of archival alienation. The first full sentence I managed to decipher was one I already knew by heart: “May God blast any one who writes a biography of me.” Unintentionally it became the name of the file in which I was collecting aphorisms and observations from the notebooks.

Peter Scott, J. M. Barrie in His Study. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Next came Barrie’s letters—astonishingly often in their original envelopes—preserved by correspondents who no doubt understood their value. Here I fared better, for Barrie knew just how unreadable his hand was and made the effort to be more legible when writing to friends and acquaintances. On my second day at the Beinecke, I came across a nondescript envelope directed to Barrie’s personal secretary, Cynthia Asquith, with no address. It was dated June 24, 1937—the day Barrie died. In it was nothing but a small scrap of paper with the words “dangerously ill” written on it. That was my first archival epiphany, and those two words—in all their heartrendingly painful awareness of death—brought James Matthew Barrie to life for me. They were probably the last words he wrote. It is no accident that we make a distinction between dead letters and a living spirit, but on that day I experienced just how powerfully handwritten words can invoke a living spirit, one that became a spectral presence in that Reading Room.

J. M. Barrie with Michael. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

There were many such days in the archive, and it was with awestruck excitement and reverence that I sat down each day to a new box of materials. In one I found Barrie’s letters to his adopted son George Llewelyn Davies. George had attended Eton and distinguished himself in sports, academics, and drama. He volunteered for service in World War I and was struck down, at the age of twenty-one, by a stray bullet on the fields of Flanders. Somehow those letters, written to George at the western front, had found their way back to Barrie. I touched them, but I did not have the heart to open them, for I recalled not only Barrie’s love for George but also the words of George’s father, Arthur Llewelyn Davies, about his son. When Arthur had cancer of the jaw, he was unable to speak after a painful operation and could communicate only through handwritten notes. On his deathbed, he jotted down the following about his five boys—what he remembered about them and how he visualized each one. Here’s what I could make out: “Michael going to school. Porthgwarra and S’s blue dress. Burpham garden. Kirkby view across valley. Buttermere. Jack bathing. Peter answering chaff. Nicholas in the garden . . . George always.”5 And then there was their mother, Sylvia’s, declaration in her will about how grieved she was to leave her boys: “I love them so utterly.” The letters felt sacred to me. I could not bring myself to open them, much as I also felt a powerful obligation to read everything available to me in an effort to make sense of the continuing enigma of J. M. Barrie and Peter Pan.

Like most scholars, I am a passionate reader and invariably develop a strong affective bond with what I write about. But the depth of feeling opened up by Barrie’s papers remained a surprise. At first, I tried hard to resist the emotional overload invoked. But it was impossible to look at pictures of the boys fishing in Scotland, to open an envelope and find locks of Michael’s hair, to read Sylvia’s will and Barrie’s transcription of it, or to look at Nico’s school report without experiencing an opera of emotions. Occasionally I worried that one of the many guards monitoring security tapes of the reading room might report the presence of a mildly unhinged user who alternated between euphoric ecstasies and depleted gloom.

Biographers can be relentless about mastering the mysteries of their subject’s life, and there is no shortage of accounts that try to pin down the exact nature of J. M. Barrie’s relationship to Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and her five boys. Peter, the third son of Arthur and Sylvia, nearly drove himself mad while assembling what he would later call “The Morgue,” a set of letters and documents, with his commentary, that tried to make sense of his family’s past and how the lives of the five boys, their parents, and J. M. Barrie intersected, connected, and were intertwined. He even went so far as to quiz his former nanny, sending her a list of questions, and to interrogate family members, friends, and acquaintances in order to get to the bottom of things.6

The key question, for Peter Davies, turned on Barrie’s feelings for Sylvia and the boys. Was his love for Sylvia romantic or platonic? Or was she nothing more to him than the gatekeeper for the five boys who were the real target of Barrie’s love and affection? Perhaps Barrie was asexual and, as his wife, Mary Ansell, broadly hinted, incapable of intimate relations? One biographer, as Peter Davies notes, reported that Barrie met Sylvia at a dinner party and was “overwhelmed” by her beauty and “intrigued by the way she put aside some of the various sweets that were handed round, and secreted them” (the sweets were for Peter). A letter to Peter Davies from a friend claimed that Barrie fell in love with Sylvia at a formal tea: “He saw, fell a victim and was utterly conquered.” Still, there is no evidence at all that their feelings for each other, even after Arthur’s death, went beyond anything but deep friendship.

Peter Davies speculated endlessly about his father’s reaction to Barrie’s love for Sylvia. Was he “a shade vexed”? Were relations between the two “strained” by the “infiltrations of this astounding little Scotch genius of a ‘lover’ ”? Was Arthur’s “irritation” deep? Did he feel “resentment” toward Barrie or “gratitude” for the many kindnesses he showed the family? On the one hand, Peter himself seems vexed by the fact that his father was constantly upstaged by Barrie’s wealth and fame; yet he also seems genuinely moved by Barrie’s altruism and selflessness. “It would be interesting to have a list of all the impoverished authors and their families whom J. M. B. helped out of his own pocket at one time and another,” he wrote.

Reading through “The Morgue” led me to the conclusion that Barrie took some secrets to the grave and that efforts to recover them are futile. A recent biography by Piers Dudgeon served as a cautionary example in substituting speculation for evidence. Focusing on the dark side of Neverland, Dudgeon paints a portrait of Barrie as a predatory monster who wormed his way into the affections of Sylvia Llewelyn Davies so that he would have access to her boys. In the archive, I discovered that nothing could be further from the truth (and reviewers of Dudgeon’s book have not disagreed with my own assessment).

To be sure, there were moments (I counted two in my many years of research devoted to Barrie’s life and works) when I worried that Barrie’s generosity was tainted by ulterior motives. If you read The Little White Bird, the ur–Peter Pan, you will feel queasy going through a description of a sleepover involving the narrator and a young neighbor boy named David. And Barrie’s replacement of his own name, “Jimmy,” for “Jenny” (the hired nanny’s sister) as the

person designated by Sylvia Llewelyn Davies in her will to raise the boys with Mary Hodgson feels wrong, although Barrie was in fact given guardianship and Sylvia no doubt linked Jenny to Mary for the purposes of day-to-day childrearing activities. Members of the extended family supported Barrie’s guardianship, not having themselves the time or means to raise five boys.

As I pondered these matters, I remembered a meditation from 1910 in Barrie’s notebooks. As soon as someone dies, he wrote, their face becomes “inscrutable—an enigma,” and they preserve their secret forever. “All have one, which nobody knows, good or bad.” Barrie no doubt had his share of secrets, good and bad. But much of him is an open book, and in it, there is love, affection, generosity, and imagination, mixed in with—as he was the first to admit—a good dose of dour moodiness and Scottish reserve. A man who fell in love with “work” at a young age (seeing his salvation in it later in life) and who declared early on that literature was his game, he loved solitude more than most. Yet he embraced real-world responsibilities, giving up his game for a time when he adopted the five Llewelyn Davies boys.

At his death, Barrie was said to have amassed a fortune greater than that acquired by any other writer through his work. Yet his philanthropic activities, in his lifetime, were also remarkable. During World War I, he subsidized a hospital and shelter for French children. He engaged in fund-raising activities, writing plays and sketches for various causes or allowing his works to be performed gratis for servicemen and war-connected charities. He even drafted a statement proposing small-scale daily economies for helping fund the war effort. For much of Barrie’s life, the royalties from Peter Pan did not add to his personal wealth but were assigned to support London’s Hospital for Sick Children on Great Ormond Street. After his death, the author bequeathed all proceeds from the work to the hospital. His legacy to that institution and to children everywhere continues and seems to grow with each new generation.

J. M. Barrie, 1905. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

St. James’s Church in Paddington, London, has a set of stained glass panels, four of which represent themes linked to the church: transportation (the first Great Western Railway built Paddington Station), leisure (Lord Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts, was baptized in the church), art (the statue of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens is located nearby), and science (the biologist Alexander Fleming lived and worked in the neighborhood). The windows were destroyed during the Blitz and rebuilt in the 1950s. (Courtesy of Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity)

1. Andrew Birkin, J. M. Barrie and the Lost Boys: The Real Story behind Peter Pan (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 202.

2. There were seven statues made from the original mold, and they are in Kensington Gardens, Sefton Park in Liverpool, and Egmont Park in Brussels; at Rutgers University in Camden, New Jersey; and in Bowring Park in St. John’s Newfoundland, Glenn Gould Park in Toronto, and Queen’s Gardens in Perth, Western Australia.

3. The Fine Art Society, Sir George Frampton & Sir Alfred Gilbert. Peter Pan and Eros: Public & Private Sculpture in Britain, 1880–1940 (London: The Fine Art Society, 2002), 3.

4. Jacqueline Rose writes in The Case of Peter Pan, or The Impossibility of Children’s Fiction (London: Macmillan, 1984) that Peter Pan has been monetized in England and converted into “toys, crackers, posters, a Golf Club, Ladies League, stained glass window in St. James’s Church, Paddington, and a 5000-ton Hamburg–Scandinavia car ferry” (103). Consumer culture has always been expert at appropriating beloved characters from children’s books, but Great Ormond Street Hospital does not in fact receive any royalties for Disney merchandise, nor has it received revenues from car ferries or a Ladies League. Barrie did profit, in his lifetime, from the sale of Peter Pan crackers and from a Peter Pan theater set design for children.

5. Llewelyn Davies Family Papers, GEN MSS 554 4/120.

6. All quotations that follow are from “The Morgue,” which can be found at the Beinecke Library, GEN MSS 554 / Box 4.

Introduction to J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan

How do we explain Peter Pan’s enduring hold on our imagination? Why do we get hooked (and I use the term with all due deliberation) when we are children and continue to remain under the spell as adults? J. M. Barrie once observed that Huck Finn was “the greatest boy in fiction,” and Huck, who would rather go to hell than become civilized, may have inspired the rebellious streak found in Peter Pan.1 Like Dorothy, who does not want to return to Kansas in The Emerald City of Oz, Huck and Peter have won us over with their love of adventure, their streaks of poetry, their wide-eyed and wise innocence, and their deep appreciation of what it means to be alive. They all refuse to grow up and tarnish their sense of wonder and openness to new experiences.

Few literary works capture more perfectly than Peter Pan a child’s desire for mobility, lightness, and flight. And it is rare to find expressed so openly and clearly the desire to remain a child forever, free of adult gravity and responsibility. Where else but in Neverland are there endless possibilities for adventure? There is, to be sure, also trouble in paradise, but before looking at unsettling and disturbing moments on the island, it is worth taking a look at what makes our hearts beat faster when the curtain rises for the play Peter Pan or when we turn the pages of the novel Peter and Wendy.

FAIRY DUST, ETERNAL YOUTH, AND PLAY: THE ATTRACTIONS OF PETER PAN

We can begin with fairy dust and flight. What child has not imagined the pleasures of soaring through the air and feeling alive with kinetic energy? Flying allows you to leave behind the safety of that nest known as home and, suddenly, to be above it all (for a change). You can make your way to the sublime—to the deep mysteries of the azure sky or to the misty beauty of fluffy clouds. Flight has its perils, as the Greek myth about Icarus makes clear. After ignoring the instructions of his father, Daedalus, about the dangers of flying too close to the sun, his wings of feather and wax melt, and he plunges into the ocean. Still, few children would pass up the opportunity to leave behind the weighty matters of daily life to experience the vertiginous pleasures of taking wing. And does any child in a book ever refuse the offer to mount a winged creature or take to the air in some other way?

Airborne children did not abound in books until after Peter Pan flew into the Darling nursery. There were magical carpets in The Thousand and One Nights and in some folktales (Baba Yaga gives one to Ivan the Fool and Yelena the Fair), but children remained earthbound on the whole, preferring travel by land or by sea. Hans Christian Andersen, with his love of avian creatures (ducklings, swans, and sparrows), is an exception, for he understood the euphoric delights of flight, and his little Kai is lifted into the air when he rides in the carriage of the Snow Queen, in the fairy tale of that title. After Peter Pan, stories proliferate about children given the chance to fly: in The Chronicles of Narnia on the back of Aslan, in Selma Lagerlöf’s Wonderful Adventures of Nils on a goose, in The Wizard of Oz in a house, in the Harry Potter books on broomsticks, and in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Swiftly Tilting Planet on a winged unicorn. These youthful aeronauts would all endorse what E. B. White’s Louis says in The Trumpet of the Swan: “I never knew flying could be such fun. This is great. This is sensational. This is superb. I feel exalted, and I’m not dizzy.”2

Barrie lived in an era when flight had finally become possible for humans. Wilbur and Orville Wright had flown their first glider in the fall of 1900 at Kitty Hawk, and by 1901 they had already developed the capacity to fly a distance of 400 feet. They soon added power and doubled that distance, but skeptics on the other side of the Atlantic were certain that the two were bluffing. The European press remained unconvinced by reports from the brothers themselves and from eyewitnesses: “They are in fact either fliers or liars. It is difficult to fly. It’s easy to say, ‘We have flown.’ ”3 In an age when airplanes had not yet moved out of the realm of fantasy and science fiction, the power to fly was all the more exquisitely thrilling.

&n

bsp; Fairy dust is of paramount importance to children, but even it has trouble competing with the mirage of eternal youth that finds embodiment in Peter Pan. The puer aeternus (Latin for “eternal boy”) found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses was a child-god named Iacchus, identified at various times with Dionysus (god of wine and ecstasy) and with Eros (god of love and beauty). Connected with the mysteries of death and rebirth, he is the god who remains forever young. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung connected the puer aeternus with the archetype of the senex, or old man. Without doubt we can find that very pairing of archetypes in Peter Pan, with Hook as something of a shadow to Peter Pan, just as the senex is the dark double of the puer aeternus. Peter’s story walks a fine line between indulging the fantasy of eternal youth and menacing readers with the specter of death—both our first death when childhood is over, and our second death when life comes to an end. What it does supremely well is to construct one boy who, by incarnating the dream of eternal youth, connects us viscerally to the human condition of mortality.

Just what makes eternal youth so appealing? In Tuck Everlasting, inspired no doubt by the story of Peter Pan, Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck makes it clear that living forever can be a curse: “ ‘I want to grow again . . . and change. And if that means I got to move on at the end of it, then I want that, too.’ ”4 J. M. Barrie would answer that question differently, and he would point to the attractions of games, play, and adventure—forever fun.

Peter Pan

Peter Pan Peter and Wendy

Peter and Wendy Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens Tommy and Grizel

Tommy and Grizel Sentimental Tommy

Sentimental Tommy When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life

When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens

The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens The Little Minister

The Little Minister Peter Pan (peter pan)

Peter Pan (peter pan) Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)