- Home

- J. M. Barrie

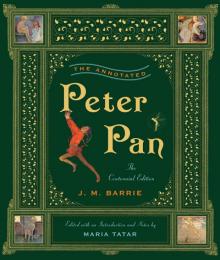

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books) Page 6

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books) Read online

Page 6

In Margaret Ogilvy, Barrie gives us a heartbreaking account of the event that plunged his mother into a state of desolation and that was to affect him profoundly as a child and as an adult. Alick, the eldest of the three Barrie sons, had opened his own private school in Lanarkshire after a successful academic career at Aberdeen University. He was joined in the new enterprise by his sister Mary, who helped with the housekeeping and taught at the school. When Alick was appointed classics master at the Glasgow Academy, he encouraged his parents to send their second son, David, to study at the school. David, handsome, studious, athletic, and known to be his mother’s favorite, was destined for the ministry, and the opportunity seemed impossible to pass up. Jamie remained the only son still at home.

The winter of 1867 was exceptionally cold, according to one account, and David had just received a pair of new skates from his brother Alick. Ever the generous spirit, David shared them with a friend. The friend tore across the ice and sped back, toppling David, who fell to the ground, hitting his head and fracturing his skull. “When the terrible news came,” Barrie reported in Margaret Ogilvy, “I have been told the face of my mother was awful in its calmness as she set off to get between Death and her boy.”9 Just before Margaret’s departure for Glasgow, a second telegram arrived with the mournful news: “He’s gone!”

Margaret Ogilvy’s life had never been easy, and she had been “delicate” after the birth of her fifth child, Agnes. Suffering then from what was likely puerperal fever (childbirth fever), she endured the death of a newborn and watched her daughter Elizabeth succumb to whooping cough. In this time of struggle, Margaret’s father died, his lungs weakened by years of inhaling quarry dust as a stonemason. For months, the family cottage, on Brechin Road, was a site of hardship, tragedy, and mourning. But Margaret Ogilvy recovered her health in 1853, and within a period of seven years, she gave birth to five more children, three girls and two boys. Then came the news of David’s accident. Losing him was more than she could bear, and she retreated to her bedroom, David’s christening robe by her side. Jamie resorted to various strategies to draw her out, becoming adept, for instance, in the art of impersonation and pantomime. Barrie describes how he developed an “intense desire . . . to become so like [David] that even my mother should not see the difference,” and he practiced in secret until he had the boy’s whistle and stance (legs apart and hands in the pockets of his knickerbockers) down pat.10 Perhaps we can find here, as in his childhood games of acting out adventures, the beginnings of his love of play-acting, performance, and theater.

In an effort to brighten his mother’s spirits by engaging her in conversation, the young Barrie exchanged stories—his tales of adventure alternating with her accounts of a childhood devoted to taking care of a younger brother and carrying out domestic chores after her own mother’s death. Barrie read eagerly and voraciously with his mother. Robinson Crusoe and Pilgrim’s Progress counted among his childhood favorites. In the lively exchanges between mother and son we can see a mirroring of the relationship between Peter and Wendy (albeit with some generational slippage): the boy enamored of adventure paired with the dutiful daughter who sews, scrubs, and tells stories. Storytelling, along with impersonating, served in the first instance as compensatory actions, helping young Jamie succeed in his “crafty way of playing physician” to the grieving mother. But they also developed into talents that served him well in adult life.

Margaret Ogilvy never really recovered from her son David’s death, but she made an effort to return to a semblance of normal life. One day she proposed to her son that he write down some of his stories. As Barrie recalls it, “the glorious idea” seemed to be his own, but it was most likely devised by his mother, who was hoping at the time to make some progress on her “clouty hearth rug.”11 A schoolmate recalls his friend’s unusual flair for storytelling:

I remember one summer afternoon when I left school in his company. . . . We turned into the Back Wynd, where we were greeted with the ring of hammer on anvil, and stopped for a minute as all boys would to watch Forsyth the smith sharpening chisels. . . . After leaving the smith’s door Jim began to tell me a story, and was fairly under way with it when we turned into The Limepots. . . . It was a “strange eventful history” told with sparkling eye, full of the minutest detail and entrancing to the listener. The story is long lost to my memory, but I recollect on my way home I pondered over the incident and thought to myself, “He’s a queer chap Jim. Where can he have got that story? It’s not like any a boy ever told.”12

Jamie was not only precocious but also prophetic. Storytelling came to be embraced as an antidote to loneliness, and he later described how, as a child, he would retreat into a dusty attic corner to write stories in order to prepare himself for the career of author:

There were tales of adventure (happiest is he who writes of adventure), no characters were allowed within if I knew their like in the flesh, the scene lay in unknown parts, desert islands, enchanted gardens, with knights . . . on black chargers, and round the first corner a lady selling water-cress. . . . From the day on which I first tasted blood in the garret my mind was made up; there could be no hum-dreadful-drum profession for me; literature was my game.13

Writing sustained and nourished the young Barrie early on and later became the only satisfactory adult substitute for childhood games. His early novels in particular have an interesting oral quality to them, as if the narrator were recounting events to an intimate rather than sitting at his desk. Playful, expansive, and chatty, works like Tommy and Grizel and The Little White Bird hark back to Barrie as boy storyteller, always with an audience in mind and always aware of the performative element in narrative.

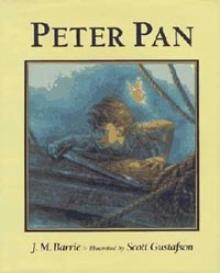

At age thirteen, Barrie attended the famous Dumfries Academy, where his brother was Inspector of Schools. The grown Barrie, in a speech given in 1924 at Dumfries, traces the origins of Peter Pan to the games played in the schoolyard there: “When the shades of night began to fall, certain young mathematicians shed their triangles and crept up walls and down trees, and became pirates in a sort of Odyssey that was long afterwards to become the play of Peter Pan. For our escapades in a certain Dumfries garden, which is enchanted land to me, were certainly the genesis of that nefarious work.”14

It was at Dumfries that Barrie read R. M. Ballantyne’s The Coral Island, a work that inspired him “to be wrecked every Saturday for many months in a longsuffering garden.” And it was there that he also discovered drama, rarely missing a performance at the town’s newly rebuilt theater: “I entered many times in my school days, and always tried to get the end seat in the front row of the pit. . . . I sat there to get rid of stage illusion and watch what the performers were doing in the wings.”15 The Dumfries Theatre Royal offered Shakespeare, and the young Barrie was treated to Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth, along with melodramas and burlesques. Immersed in this theatrical culture, the boy scholar wrote his own play, Bandelero the Bandit (Bandelero, like Peter, was a composite of Barrie’s “favorite characters in fiction”), which achieved some notoriety after being performed for the public. A clergyman who had attended one of the performances denounced it as “grossly immoral.” Many local worthies rose to the defense of the young thespians against the fulminations of a “certain class of pulpit bigots,” and a second successful season followed the first for the Dumfries Amateur Dramatic Club.16 In one production (a play adapted from a story by James Fenimore Cooper), the young Barrie played six different roles. He later looked back at the five years at Dumfries as “probably the happiest of my life.”

After finishing his education at the academy, Barrie went on, reluctantly, to the University of Edinburgh for the study of literature. Far more appealing than the drab academic life there (“students occasionally died of hunger and hard work combined”) was the world of journalism. The offer of three pounds a week to write leaders for the Nottingham Journal, after completing his M.A. degree at Edinburgh, was irresistible.17 Determined to make his living by the pen, Barrie was relentless in seek

ing outlets for his prose. A series of articles for the St. James’s Gazette published under the title “Auld Licht Idylls” that described life in the fictional village of Thrums (modeled on his native Kirriemuir) gave Barrie the courage to move to London and begin the “hard campaign” of establishing himself as a writer. An auspicious sign came on his arrival in the city: the first sight to greet him was a placard advertising his article “The Rooks Begin to Build” in the St. James’s Gazette. “I remember,” he reminisced in the third person, “how he sat on his box and gazed at this glorious news about the rooks.” Barrie looked back on that moment as the beginning of the great romance of his life.

Book jacket for Barrie’s 1887 first novel, Better Dead, which moved in the genre of the “shilling shocker.” (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Working as a freelance journalist in London, Barrie developed a homespun style, taking up topics that cosmopolitan audiences had never before encountered in the pages of the British Weekly, the Era, or Punch. “On Running After One’s Hat,” “A Plea for Wild Flowers,” “The Joys of Wealth by a Bloated Aristocrat,” and “On Folding a Map” were among the projects he undertook. With quirky humor and wayward charm, he drew even sophisticated readers in. But Barrie himself recognized that his own voice rarely came through, for he had a habit of impersonating others: “Writing as a doctor, a sandwich-board man, a member of the Parliament, a mother, an explorer, a child . . . a professional beauty, a dog, a cat. He did not know his reason for this, but I can see that it was to escape identifying himself with any views. In the marrow of him was a shrinking from trying to influence anyone, and even from expressing an opinion.”18 Characteristic of Barrie is the resistance to using pronouns consistently. In his newspaper articles, as in his fiction, he moves seamlessly from “I” to “he” or from “we” to “you,” never allowing himself to be pinned down to one identity or point of view.

Barrie’s sprightly journalistic essays were collected under the title Auld Licht Idylls and published in 1888. The anthology formed a launching pad for more sustained novelistic efforts, and A Window in Thrums, published to critical acclaim two years later, sold well. Both works sought to capture a world that was rapidly vanishing in the face of industrialization and urbanization. Thrums, a thinly disguised Kirriemuir, offered an opportunity for nostalgic meditation, reminding its readers that rural life had a kind of dignified communal rootedness even in the midst of hardship and poverty. Inspired by his observations of the daily lives of the weavers, artisans, and peasants in his own town, Barrie offered accurate, unsentimental portraits that rang so true that his mother hid the book whenever she received visitors.

Barrie’s next novel established him as a major voice in the literary world, and suddenly his name began to appear in the company of Hardy, Kipling, and Meredith. The Little Minister tells the story of a scandalous relationship between Gavin Dishart, a cleric assigned to Auld Licht church in Thrums (with a pious mother named Margaret), and Babbie, a beautiful and mysterious Gypsy girl betrothed to the sinister Lord Rintoul. Torn between convention, piety, and responsibility and the lure of an exotic, forbidden romance, Dishart struggles to maintain his respectability even as he succumbs to the charms of a seemingly otherworldly creature—she had “an angel’s loveliness.”

The novel began its run as a serial in the periodical Good Words and was published in London in 1891 as one of the last “three deckers,” works that appeared in a three-volume format. It was adapted for the stage six years later and made into five feature films (the last a 1934 melodrama starring Katharine Hepburn). The Little Minister featured what Barrie called “the shortest hero in fiction.” In the preface, he added with a touch of pride that Dishart is in fact “the only short hero” ever. “Were all the heroes of the novels to meet on some vast plain, you could pick him out at once, not because he was preaching to the others (though that is what he would be doing), but solely because of his lack of inches.”19

The Little Minister secured Barrie’s literary reputation in the Anglo-American literary world. When the play was performed in the United States (where numerous pirated versions of the novel were in circulation), it broke records on Broadway at Frohman’s Empire Theatre with Maude Adams in the lead. A number of plays followed in rapid succession, despite Barrie’s stated belief that drama was a “walk of literature I at first trod rather contemptuously,”20 among them Walker, London, staged in 1892. For that work, Barrie had hired a young actress named Mary Ansell to play the second lead, and the two began dining together at fashionable restaurants. The courtship, followed closely by London gossip columnists, took many twists and turns. It was interrupted for a period of several months by another tragic event in Barrie’s life, when his sister’s fiancé was thrown from a horse and died. The horse had been a gift from Barrie himself, who was stricken with grief and guilt in the months to come.

The first installment of My Lady Nicotine, which begins by comparing smoking to matrimony. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Mary Ansell, 1896. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

J. M. Barrie and Mary Ansell were both in their thirties at the beginning of their courtship, and Mary became increasingly perplexed that there was no proposal, no plan, no decisive turn in their relationship. Yet Barrie was all the while wrestling with questions about his future with Mary. He retreated at one point to the Cornwall estate of his friend Arthur Quiller-Couch to write a story about a character called Bookworm. There, while delighting in the company of the three-year-old Bevil Quiller-Couch, Barrie outlined the main features of a character in a play that was to be called The Professor’s Love Story. In it he expressed some deep misgivings about a man who seeks to remain a lifelong bachelor. Bookworm’s doctor asserts that marriage will turn his life around and lead to his “remaking”: “He has got so sunk in books, they’ll drown him, he’ll become a parchment, a mummy.”21

My Lady Nicotine offered a series of vignettes on smoking. Barrie himself smoked a pipe all his life and suffered from a persistent percussive cough. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

A decade later, in 1904, even after his marriage to Mary, Barrie continued to fret about his sense of being more literary than real. He delivered a speech to the Royal Literary Fund and wondered “whether we are really here or whether this is only a chapter in a book; and if it is a chapter in a book I wonder which of us all is writing it.”22 He reflected often on the question of a divided self in ways that dovetail perfectly with modernist notions of split consciousness and existential anxieties about hyperintellectualization. Literature had truly become his game, and there is a sense in which scripts, roles, pantomimes, masks, and mimicry had taken over his life. There is no doubt that Barrie saw himself as self-contained in a way that few other people were—including his fellow Scots, with what he had described as their shuttered windows. If we add to that the fact that the marriage to Mary was more than likely never consummated, it becomes clear why Barrie hesitated for so long.

Years earlier, Barrie had felt misgivings of a different kind. In an article written for the Edinburgh Evening Post entitled “My Ghastly Dream,” he describes a recurring nightmare that changed in content over the years and gradually took the form of anxieties about wedlock:

When this horrid nightmare got hold of me, and how, I cannot say, but it has made me the most unfortunate of men. . . . At school it was my awful bed-fellow with whom I wrestled nightly while the other boys in the dormitory slept with their consciences at rest. It assumed shape at that time: leering, but fatally fascinating; it was never the same, yet always recognisable. One of the horrors of my dream was that I knew how it would come each time, and from where. . . . My weird dream never varies now. Always I see myself being married, and then I wake up with the scream of a lost soul. . . . My ghastly nightmare always begins in the same way. I seem to know that I have gone to bed, and then I see myself slowly wakening

up in a misty world.23

Barrie came to a decision at last and traveled north in March 1894 to break the news to his mother that he was engaged to an actress. During the visit, he developed a case of pneumonia that turned into pleurisy, and he was more seriously ill than ever before in his life. Mary Ansell rushed to his bedside to assist in the convalescence, and when Barrie recovered, the couple set a wedding date. On July 9, 1894, James Matthew Barrie and Mary Ansell married and traveled to Switzerland for their honeymoon. There, Barrie purchased a St. Bernard puppy as a wedding present for his wife. The dog, shipped off to London, was named Porthos after the St. Bernard (in turn named after one of the three musketeers) in George du Maurier’s novel Peter Ibbetson, and he became like a child to the couple. Their new home, at 133 Gloucester Road, in London, was conveniently close to Kensington Gardens, where Barrie and his large dog (who could stand on his hind legs and box with his master) became a prominent odd couple attracting the attention of children at play.

Porthos served more functions than one might imagine in the lives of the Barries. In her book Dogs and Men, Mary described painful “silent meals” at home, when “the mind of your man is elsewhere”: “Just when the silence is becoming unbearable, your dog steps in and attracts your attention. . . . And with an adoring glance he rewards you for the titbits you pop into his mouth. Your heart begins at once to warm up again. The whole balance of life is restored.”24 With no children and with an acting career that had come to an end, Mary had to resort to the companionship of dogs and to the domestic pleasures of redecorating, focusing on homes and gardens, first in London, where she made improvements to the homes on Gloucester Road and, later, Leinster Corner. She would also refurbish a cottage in Surrey adjacent to Black Lake, the scene of her husband’s pirate games with the Llewelyn Davies boys.

Peter Pan

Peter Pan Peter and Wendy

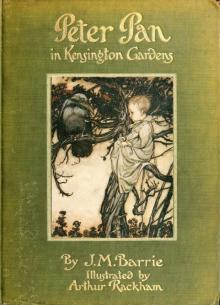

Peter and Wendy Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens Tommy and Grizel

Tommy and Grizel Sentimental Tommy

Sentimental Tommy When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life

When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens

The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens The Little Minister

The Little Minister Peter Pan (peter pan)

Peter Pan (peter pan) Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)