- Home

- J. M. Barrie

Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Page 2

Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Read online

Page 2

1917 Dear Brutus, Barrie’s play about a group of characters who enter a magic wood and are given the chance to turn back time and reshape their lives, debuts on October 17 at the Wyndham’s Theatre. After one of the greatest adventures of all time, Ernest Shackleton’s expedition to Antarctica is rescued. T. S. Eliot’s Prufrock and Other Observations is published.

1919 Barrie becomes rector of St. Andrews University.

1920 His play Mary Rose is first performed on April 22 at the

Haymarket Theatre in London. The play, which deals with aging, youth, death, and memory, enjoys enormous popularity among an audience of theatergoers who are mourning a generation largely wiped out by World War I.

1921 Barrie’s favorite adopted son, Michael, drowns in a millpond at Oxford; his death may be a suicide. Shall We Join the Ladies? opens on May 27 in celebration of the opening of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

1922 Barrie is awarded the Order of Merit. Eliot’s The Waste Land and Joyce’s Ulysses are published.

1924 A silent film of Peter Pan appears; Barrie has written a scenario for a film, but his version is not used.

1927 Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse is published. Charles Lindbergh flies across the Atlantic Ocean alone.

1928 Peter Pan is published as a single volume and in The Plays of j M. Barrie; it carries Barrie’s dedication to the five Davies boys. Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall is published.

1929 Barrie gives all rights to and royalties from Peter Pan to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Sick Children. Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That is published.

1930 Barrie receives an honorary degree from Cambridge University and is appointed chancellor of Edinburgh University. W. H. Auden’s Poems is published.

1936 The Boy David, Barrie’s last dramatic work and his only play to premiere in his native Scotland, opens at the King’s Theatre in Edinburgh on November 21 and in London three weeks later. The piece reflects aspects of his own life, including the untimely death of his brother David; it is not a success.

1937 On June 19 J. M. Barrie dies. He is buried beside his family in Kirriemuir cemetery.

INTRODUCTION

At six years old, James Matthew Barrie believed he was his mother’s last hope. Inconsolable after the sudden death of her son David, who had fractured his skull in a skating accident, Barrie’s mother fell ill with grief. In his memoir about his mother, Margaret Ogilvy, Barrie recalls how his sister Jane Ann came to him “with a very anxious face and wringing her hands” and told him to go quickly to his mother “and say to her that she still had another boy” (Barrie, Margaret Ogilvy, see p. 12; see “For Further Reading”). Barrie went that day and for many days afterward to his mother’s bed, where, through jokes and antics, he strove to make her laugh. He even kept a record of her laughs on a piece of paper. The first time he slipped the laugh chart into her doctor’s hand, it showed that his mother had laughed five times. When the doctor saw the chart, he laughed so hard that the young Barrie exclaimed, “I wish that was one of hers!” (p. 14). The doctor took sympathy on him and suggested he show the chart to his mother, at which point she would laugh again and the five laughs would increase to six. Barrie writes, “I did as he bade me, and not only did she laugh then but again when I put the laugh down, so that though it was really one laugh with a tear in the middle I counted it as two” (p. 15).

Barrie’s sister said that in addition to making his mother laugh he needed to encourage her to talk about her dead son. While Barrie couldn’t see how this would make her “the merry mother she used to be” (p. 15), he was advised that if he could not do it, “nobody could,” which made him “eager to begin.” At first, he often was jealous of his mother’s “fond memories” and would interrupt them with the cry “Do you mind nothing about me?” But this resentment did not last. Instead, Barrie countered his jealousy by trying to become so like his dead brother that his mother would not see the difference. He asked Margaret many artful questions about David, and he practiced imitating him in secret. For example, his mother told him that David had “such a cheery way of whistling ... with his legs apart and his hands in the pockets of his knickerbockers” (p.16) and that it always brightened her workday. One day, after Barrie had learned his brother’s whistle (which took much practice), he disguised himself in a suit of David’s dark gray clothes and slipped into his mother’s room. With his legs stretched wide apart, and his hands plunged deep into his knickerbockers, he began to whistle.

No matter what Barrie’s successes were in coaxing his mother to laugh, he could not make her “forget the bit of her that was dead” (p. 19). Often she fell asleep speaking to David. Even while she slept, her lips moved and she smiled as if the dead boy had come back to her. Sometimes when she woke, he vanished so suddenly that she would rise bewildered, saying slowly, “My David’s dead!” Or perhaps David “remained long enough to whisper why he must leave her now, and then she lay silent with filmy eyes.” Just as his mother was perpetually haunted by her dead son, Barrie himself became preoccupied by a ghost child who kept returning to him from the other side of the grave. Most famously, this ghost appears in the shape of Peter Pan—a boy who materializes from the world of children’s dreams.

The combination of laughter and tears, or the effort to make his audience laugh in the face of tragedy, distinguishes all of J. M. Barrie’s writing. We encounter the most flawless example of this mixture of humor and heartbreak in Peter Pan—the story of a never-aging boy who takes other children on fantastic adventures and is eventually abandoned by them. “All Barrie’s life,” wrote Roger Lancelyn Green, “led up to the creation of Peter Pan, and everything that he had written so far contained hints or foreshadowings of what was to come” (J. M Barrie, p. 34).

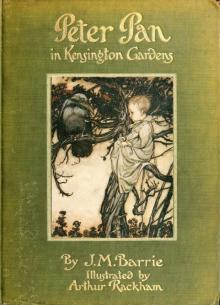

The idea behind Peter Pan first appeared in Tommy and Grizel, a novel that Barrie published in 1900 as a sequel to Sentimental Tommy, which had come out in 1896. In Tommy and Grizel, the main character, Tommy, contemplates writing a story about a boy who hates the idea of growing up. Like the character in his story, Tommy cannot make the passage from childhood to adulthood; he is doomed to love his wife, Grizel, in exactly the same way that he loves his sister Elspeth. Peter Pan first appears by name in a strange novel, The Little White Bird, that Barrie published in 1902. Written for adults, the book is narrated by Captain W—, a middle-aged bachelor and member of the Junior Old Fogies’ Club. Like Barrie, he has a St. Bernard dog named Porthos. As the narrative develops, Captain W—invents and then kills off a son in order to become close to a little boy named David. Six chapters of the book consist of a story that the Captain and David create together: the tale of Peter Pan’s birth and his escapades with the birds and fairies in Kensington Gardens. Peter is much younger in this novel than in later stories—in spirit, he is only one week old. In 1906 Barrie extracted the six chapters about Peter, and they were published, accompanied by Arthur Rackham’s illustrations, under the title Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens.

Appearing the same year as The Little White Bird, Barrie’s play The Admirable Crichton opened in 1902. Drama scholar Harry Geduld calls The Admirable Crichton Barrie’s “comedic masterpiece” (Sir James Barrie, p. 120). In it, a wealthy family and its servants are stranded on a “wrecked island,” where the rules of power reverse, only to restore themselves completely when the group is rescued at the end. The Admirable Crichton resembles Peter Pan in that it begins realistically, converts into a fantasy with the shipwreck, and returns to normalcy in the concluding scenes. On the island the butler (Crichton) becomes the group’s leader, and Lady Mary, the aristocratic daughter of his employer, falls passionately in love with him. Two years later, she is about to marry him—and then the marooned group is discovered. In act 4, Lady Mary loses all interest in Crichton when the power relations reverse a second time. While the play is a comedy, it is also poignant, for the natural and truthful love that the characters feel on the island proves impossible to sustain in real life.

Written just b

efore Peter Pan, Barrie’s play Little Mary was first performed in 1903. Little Mary is the story of a girl named Moira (Wendy’s full name in Peter Pan is Wendy Moira Angela Darling) who is able to cure illnesses with the aid of an invisible medium called Little Mary. Moira becomes known throughout society as the Stormy Petrel, the name of a species of seabird that is used for someone who appears at the onset of trouble. The play is quite entertaining until Moira’s strategy is at last revealed at the end of the final act—she has simply changed her patients’ diets, for her grand-father had proved that we are what we eat. (Such a twist was fitting in that “Little Mary” was Moira’s pet name for “stomach.”) Because of the play’s unfortunate climax, Little Mary was mocked by reviewers and satirized in comic strips, although it ran for 207 performances. It may have done better if, like Peter Pan, it had permitted the existence of a certain degree of magic. It was not until the following year that Barrie more than made up for Little Mary with Peter Pan; or, The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up, which was first performed at the Duke of York’s Theatre in 1904.

The story of Peter Pan developed in the company of the five sons of Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies: George, Jack, Peter, Michael, and Nicholas (Nico). Barrie first met this family in 1897. At the time, he was married to Mary Ansell, an actress who had played one of the girls in his 1892 play Walker, London. Their marriage of three years was an unhappy one, troubled by Barrie’s likely impotence and his consequent lack of interest in sex. Although both adored children, the marriage remained childless. One day while walking his dog, Barrie met four-year-old George Llewelyn Davies and George’s younger brother Jack. George and Jack took an interest in Barrie’s dog, and Barrie began meeting the children every day in Kensington Gardens.

Barrie’s involvement with the family grew intimate—he began to visit the Davies home for tea and for dinner. After he met their baby brother, Peter, Barrie began to weave Peter’s name into the stories he made up and performed for George and Jack. In one of these stories, all babies are birds before they turn into human beings; Peter was a child who had not completely stopped being a bird and therefore could still fly. Peter Llewelyn Davies’s failure to demonstrate his flying ability compelled Barrie to invent a fictional version of him—Peter Pan.

As the Davies boys grew older, Barrie converted his early tales about Peter, in which Peter was only one week old and played with the birds and fairies in Kensington Gardens, into stories about pirates and fantasy islands. Michael Llewelyn Davies was born in 1900—the first child in the family whom Barrie knew from birth. In 1901 the Davies family summered in Surrey a short distance away from the house on the Black Lake that the Barries had purchased the previous year. Barrie played with the boys all that summer, and their fantasy games supplied material for a book called The Boy Castaways of black Lake Island (another early version of Peter Boy Castaways of Black Lake Island (another early version of Peter Pan). The book—supposedly written by four-year-old Peter Llewelyn Davies (even though it was purportedly “published” by J. M. Barrie)—consisted of a preface and thirty-six captioned photographs. Barrie put together two copies of the manuscript, one of which he gave to Arthur Llewelyn Davies, who promptly lost it. At Christmas that same year, a visit to the theater with the Davies boys to see Bluebell in Fairyland gave Barrie the idea that he might write his own play for children.

On November 23, 1903, the day before the birth of Nicholas Llewelyn Davies, Barrie began to work seriously on the play that would later become Peter Pan. At first, it was simply called “Anon. A Play.” Barrie finished the first draft of the Peter Pan play on March 1, 1904, but he was worried that his American producer, Charles Frohman, would not like it. Peter Pan was an incredibly expensive show to put on, requiring massive sets and a cast of more than fifty, including a dog, a fairy, a crocodile, an eagle, wolves, pirates, and redskins, and at least four cast members would be required to fly. It was also unclear what sort of audience Barrie had in mind for the play—it seemed to be oriented to children, but the dialogue was quite sophisticated. The first version of the play combined harlequins and columbines (from the old pantomime tradition) with pirates and redskins, and it curiously blended outrageous farce with grave sentimentality. Barrie first showed his play to Beerbohm Tree, one of the most famous actors and directors of the period. Tree’s intricate and luxurious productions at His Majesty’s Theatre had won him a substantial reputation for excessiveness, and Barrie thought he might be willing to put on Peter Pan if Frohman rejected it. However, Tree did not at all approve of the play; he wrote the following assessment and sent it to Frohman:

Barrie has gone out of his mind.... I am sorry to say it, but you ought to know it. He’s just read me a play. He is going to read it to you, so I am warning you. I know I have not gone woozy in my mind, because I have tested myself since hearing the play; but Barrie must be mad (quoted in Maude Adams: An Intimate Portrait, p. 90).

Tree’s reaction intimidated Barrie, who prepared another, much more realistic drama, Alice Sit-by-the-Fire, hoping it would give him negotiating power. When he met with Frohman in April 1904, Barrie gave him two works—Peter Pan, which he had retitled The Great White Father, and Alice Sit-by-the-Fire. He told Frohman he was sure the former would not be a commercial success, but it was a dream-child of his, and he was so eager to see it on stage that he would provide a second play to make up for the losses the first would incur. While Frohman thought Alice Sit-by-the-Fire was rather entertaining, he loved everything about The Great White Father (except for the title). Barrie had assumed Peter Pan would be played by a boy. But Frohman suggested that Peter should be played by American actress Maude Adams, who at the time was thirty-three years old. After all, Peter Pan was the star role. If Peter were to be played by a boy, the ages of the Lost Boys would have to be scaled down, and in England actors under fourteen years old could not perform after 9 P.M. Even though Maude Adams was not available until the following summer, Frohman was so anxious to see the play produced that he directed his London manager, William Lestocq, to go ahead at once with a West End production that would open in time for Christmas.

Once rehearsals for Peter Pan began at the Duke of York’s in late October 1904, an aura of secrecy began to surround the play. Few cast members knew the play’s title or story—most were given only those pages pertinent to their parts. Frohman’s decision to have Maude Adams play Peter in America meant that a woman should also fill the role in the London production. Thirty-seven-year-old Nina Boucicault seemed a suitable choice—she had just played Moira in Little Mary, and her brother Dion was directing Peter Pan. For the part of Wendy, Barrie chose Hilda Trevelyan (who had replaced Nina Boucicault as Moira in a touring production of Little Mary). And he hired George Kirby’s Flying Ballet Company to devise the flying apparatus. Kirby invented a revolutionary new harness to allow for difficult flight movements, requiring extraordinary skill on the part of the actors, who had to endure an exhausting two weeks of training. The coat of Barrie’s Newfoundland dog Luath (a replacement for his Saint Bernard, Porthos) was reproduced for the actor playing Nana, and the Davies boys’ clothes were duplicated for those of the Darling children and the Lost Boys.

The night before the play was to open, an automatic lift broke down, ruining much of the scenery. Consequently, the opening had to be postponed from December 22 to December 27. Because of other problems, Barrie had to cut the final twenty-two pages of the script; he rewrote what was at that point the fifth modified conclusion. By opening night, everyone expected a minor catastrophe. When Peter endeavors to save Tinker Bell’s life, he shouts to the audience, “Do you believe in fairies? If you believe, wave your handkerchiefs and clap your hands!” Because Barrie was convinced that the play would be a disaster and that this line would be greeted with silence from the stylish adult audience, he had arranged with the musical director to have the orchestra put down their instruments and clap. As it turned out, when Nina Boucicault asked if anyone believed in fairies, the audience applauded so enthusi

astically that she burst into tears. The first night ended with many curtain calls and rave reviews. Even Beerbohm Tree’s half-brother, Max Beerbohm, complimented Barrie in the Saturday Review: “Mr. Barrie is not that rare creature, a man of genius. He is something even more rare—a child who, by some divine grace, can express through an artistic medium the childishness that is in him” (quoted in Birkin, J. M. Barrie and the Lost Boys, pp. 117-118).

In its stage history, Peter Pan displays a good deal of gender fluidity. Theatrical cross-dressing originates in the traditions of pantomime, where gender swapping is essential—actresses typically portray the leading young male heroes in these shows, and men often play the parts of women. Traditionally, in Peter Pan the same actor would play both Mr. Darling and Captain Hook, although originally Barrie asked that Hook be played by a woman—the same woman, in fact, who played Mrs. Darling. And, of course, the show has a long history of casting women in the role of Peter. As described above, Nina Boucicault created the title role in London, and Maude Adams was Peter in New York. With rare exceptions, women would continue to act the part of Peter for almost fifty years. In the 1954 musical production of the play (which was later filmed for television and broadcast seven times between 1955 and 1973), Mary Martin played Peter. Two major Broadway revivals starred Sandy Duncan, in the late 1970s, and gymnast Cathy Rigby, in the 1990s.

In 1938 an American production cast a male, Leslie C. Gorall, as Peter Pan, and in 1952 a German production put a male in the role. The English did not break their cross-dressing tradition until 1982 when Trevor Nunn and John Caird produced their version of Peter Pan at the Barbican Theatre in London.

Although elements of Peter Pan’s story appeared in Barrie’s Tommy and Grizel and The Little White Bird, Barrie did not officially write his novel about Peter Pan until 1911, when he published Peter and Wendy. (The original copyright expired in 1987, and the novel is now known by the title Peter Pan.) In terms of plot, it closely resembles the play. One exception is an epilogue to the play, which Barrie called “An Afterthought,” where we are given a glimpse into the future, when Wendy is married and the mother of a little girl. This postscript was performed only once in Barrie’s lifetime (on February 22, 1908)—he insisted that it remain a one-night-only addition. However, he included the scene about the future in the novel, where it appears as chapter XVII, “When Wendy Grew Up.” “An Afterthought” in its original form was first published as part of the play in 1957, twenty years after Barrie’s death.

Peter Pan

Peter Pan Peter and Wendy

Peter and Wendy Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens Tommy and Grizel

Tommy and Grizel Sentimental Tommy

Sentimental Tommy When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life

When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens

The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens The Little Minister

The Little Minister Peter Pan (peter pan)

Peter Pan (peter pan) Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)