- Home

- J. M. Barrie

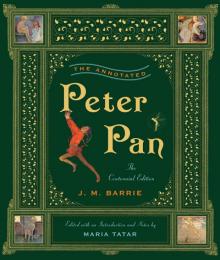

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books) Page 11

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books) Read online

Page 11

9. calculating expenses. Mr. Darling is consumed by anxieties about finances, and he repeatedly worries about the costs of children. The intensity of those anxieties suggests that children represent more than a financial threat. Not only do the children demand attention from Mrs. Darling, they will also grow up, displacing the older generation.

10. “one pound seventeen.” Mr. Darling is calculating that he has one pound and seventeen shillings. “Three nine seven” is three pounds, nine shillings, and seven pence, and half a guinea equals one pound. Mr. Darling is not so much greedy or mercenary as he is anxious about family finances. He hopes to capitalize on Peter Pan’s shadow: “There is money in this, my love. I shall take it to the British Museum tomorrow and have it priced.” As Cecil Eby points out, Mr. Darling has “the soul of a Dickensian bookkeeper” who measures the world “with a stick calibrated in pounds and shillings” (131).

11. “George.” The names of the male members of the Darling family are drawn from the families of Arthur Llewelyn Davies and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies, née du Maurier. George is named after Sylvia’s brother and the firstborn in the Llewelyn Davies family. (He was called Alexander in early drafts of the play.) Michael is named after the fourth son of Arthur and Sylvia. And John is named after the second son, nicknamed Jack.

John, Wendy, Michael, and Nana. (Peter Pan and Wendy by J. M. Barrie, Retold for the Nursery by May Byron. Illustrated by Kathleen Atkins)

12. this nurse was a prim Newfoundland dog, called Nana. The dog Nana as nurse introduces the twin themes of play and masquerade, with dogs in the roles of humans, and vice versa (Mr. Darling will later reverse roles with Nana and move into her house). As in the child’s world, the division between humans and animals remains fluid. Barrie himself owned a St. Bernard named Porthos, and in the Disney version of Peter Pan, Nana is a St. Bernard. Porthos died in 1902, and Barrie’s next dog was a Newfoundland named Luath, who became the model for stage Nanas. Luath was anything but prim, and he had what one Barrie biographer refers to as a “passion for motoring.” His name may come from the infamous forged epic poem penned by the Scottish writer James Macpherson. In that work, known as Ossian, Cuchullin’s dog is called Luath. Luath may also have been named after a collie in Robert Burns’s “The Twa Dogs.” One expert on Newfoundland dogs reports that “In addition to being something of a status symbol, Newfoundlands were also employed as canine nannies and personal companions, and saw great popularity as gun dogs” (Bendure 70).

In the introduction to the play Peter Pan, Barrie pointed out that “at one matinee we even let him [Luath] for a moment take the place of the actor who played Nana, and I don’t know that any members of the audience ever noticed the change, though he introduced some ‘business’ that was new to them but old to you and me.”

13. Kensington Gardens. In Barrie’s time, Kensington Gardens had a rustic quality to it, with sheep grazing on its lawns. Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens are divided by the Long Water and the Serpentine. Barrie lived at 133 Gloucester Road, just a short distance from Kensington Gardens. There he took daily walks with Porthos that led to the meeting with the Llewelyn Davies brothers, who lived at 31 Kensington Park Gardens. To honor the fame he brought to that park, Barrie was presented with a key to the gate of Kensington Gardens. Viscount Esher, secretary to His Majesty’s Office of Works, made the arrangement, and Barrie, with characteristic mock gravity, vowed never to misuse his privileges.

14. rhubarb leaf. The rhubarb root was used to treat infant digestive problems and was also a traditional remedy for constipation and diarrhea. First grown as a market crop in England in 1810, rhubarb gained swiftly in popularity over the next century. Barrie no doubt meant rhubarb root rather than leaf, since rhubarb leaves contain toxic substances, including oxalic acid.

Postcard of Gerard du Maurier as Mr. Darling in Peter Pan. Nana is played by Arthur Lupino. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

15. footer. In England, soccer is known as football, and sometimes referred to as “footer” or “footie.”

16. she did not admire him. Mr. Darling’s insecurities and need for respect, even from the family dog, are referred to repeatedly.

17. There never was a simpler happier family. The statement may possibly be an allusion to the famous first sentence of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Barrie refers to Tolstoy often in his essays, citing him approv ingly, for example, on the effects of smoking in “The Wicked Cigar.”

18. Peter Pan. When Captain Hook asks, “Pan, who and what are thou?,” Peter exuberantly replies: “I’m youth, I’m joy . . . I’m a little bird that has broken out of the egg.” Barrie, when asked by Nina Boucicault (the first actress to play the role of Peter Pan) for some hints about the character, refused to tip his hand much: “Peter is a bird . . . and he is one day old” (Hanson 36). The allusion to hatching may refer to the antics of the British actor John Rich, who portrayed Harlequin hatching from an egg onstage at the beginning of his performances. Peter, like the Harlequin figure, is something of a trickster and magician and gifted in the art of masquerade and mimicry. And his surname may be inspired not just by the Greek god but also by “panto,” the name commonly used to describe the extravagant theatrical pantomimes staged for children in the Victorian era. Like those pantomimes, Peter Pan has a Principal Boy, a Principal Girl (Wendy), a Demon King (Hook), and a Good Fairy (Tinker Bell). The original productions of Peter Pan followed the pantomime tradition of having villains enter from stage left while other (good) characters entered from stage right. For the first few performances in London, Columbine and Harlequin ended the play with a dance.

In Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, Peter Pan is a baby boy who rides a goat and plays the syrinx (the Greek Pan’s musical pipe with seven reeds). He is described as a “little half-and-half.” He is neither “exactly human” nor “exactly a bird” and is designated as a “Betwixt-and-Between” (17). The older Peter is sometimes depicted with the lagobolon, a hook for catching small game and controlling herds (note the connection to Captain Hook).

The original Greek Pan was part goat, part god, joy and “panic” combined, and he was often depicted with the syrinx, his pipes, or a lagobolon. As the son of Hermes and the daughter of the shepherd Dryops, he possessed a mercurial temperament and lightning-rapid mobility. He was also associated with the rural delights of pastoral life. In The Golden Bough, the Scottish anthropologist Sir James Frazer describes Pan as a goatish demigod allied with Dionysus as well as with “Satyrs, and Silenuses” (538). Pan also displays a kinship with Icarus, Phaeton, Hermes, Narcissus, and Adonis. Hermes, in particular, is closely linked with Peter Pan, for he is at once trickster, psychopomp (leading souls to Hades), and dream maker. The mythological Pan inspires terror through his association with excess, intoxication, and licentiousness.

Barrie’s hero owes something to the cultural mania about Pan in the Edwardian era. Kenneth Grahame immortalized Pan as the “Piper at the Gates of Dawn” in The Wind in the Willows (1908). In an essay entitled “Pan’s Pipes” (1881), Robert Louis Stevenson proclaimed that “Pan is not dead.” Pan is the hero of Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906), and Dickon in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Secret Garden is a Pan figure, a good-natured rural savior who communes with nature. In E. M. Forster’s “Story of a Panic” (1904), the death of Pan is mourned.

Barrie eventually settled on using Peter Pan as his title, but he had also contemplated other possibilities, among them “Anon,” “Fairy,” “The Great White Father,” and “The Boy Who Hated Mothers.”

19. tidying up her children’s minds. Mrs. Darling engages at night in the supremely maternal activity of tidying up her children’s minds, which, as we discover, are filled with clutter collected in the course of the day. The parallels set up between housekeeping (cleaning drawers) and child rearing (tidying up minds) reinforce the notion that both are women’s work. Unlike Walter Benjami

n, who endorsed the revolutionary messiness of the child’s mind, Mrs. Darling is a true Victorian at heart, taming and domesticating her children by concealing everything that does not conform to her standards of innocence and sweetness. There is no evidence that Barrie knew of Freud’s work, but many of his ideas seem to capture in poetic terms concepts such as repression, as developed in The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

20. a map of a person’s mind. Only a few years earlier, Freud had begun mapping the mind that Barrie describes here. Barrie’s description of a “child’s mind” and his inventory of what it contains modulates into an account of what Neverland looks like. Neverland is a domain of febrile activity and eternal return (“keeps going round all the time”), animation, and anarchy. Combining elements both fanciful and factual (stories and the residues of everyday experience), it contains gnomes, savages, and princes but also verbs that take the dative, fathers, and the round pond. To adults, the febrile activity and emotional overload of the child’s mind make it appear alarmingly unstable. But the heterogeneous enumeration of what is in Neverland also pays tribute to the richness of the child’s imagination and memory.

21. Neverland is always more or less an island. “Never-Never” was a term used in the nineteenth century to describe uninhabited regions of Australia. It is still used today to describe remote regions in that country. In 1904, the British actor and playwright Wilson Barrett published a work called The Never-Never Land. Its cover was decorated with kangaroos, and the first sentence read: “At Woolloogolonga Gully, in the Never-Never Land of Queensland, Australia, it was one hundred and twenty in the shade.”

Peter Pan’s island was called “Never Never Never Land” in the first draft of the play, but was soon abbreviated to “Never Never Land” in the performed version. When Peter Pan was first published as a play, the island became “The Never Land,” and in Peter and Wendy it is most often referred to as “Neverland.” The term has sometimes been seen as a command—never to land. As a place where lost boys sleep, it also becomes the domain of the dead, with the boys moving almost directly from the womb to the tomb.

Neverland may be modeled on Tír na nÓg, the most prominent of the Otherworlds in Irish mythology, an island that cannot be located on a map. Mortals can reach it only by invitation from one of the fairies residing on it. A place of eternal youth and beauty, it is a utopian land of music, pleasure, happiness, and eternal life.

Sarah Gilead sees the “never” in Neverland as a form of “stark denial” in its double meaning: “on the one hand, the refusal of the self to conceive of its own end and, on the other, the absolute reality of death” (286). She points out that Neverland is a “realm of death under the cover of boyish fun and adventure.” That the boys live underground in houses that resemble coffins offers further evidence of Neverland as the Underworld.

Peter and Wendy, like Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), Johann Wyss’s Swiss Family Robinson (translated into English in 1814), and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883), belongs to the genre of the island fantasy. In Barrie’s day, there were also countless Robinsonnades, along with parodies, prequels, and sequels to Robinson Crusoe, among them R. M. Ballantyne’s The Dog Crusoe (1861) and W. Clark Russell’s The Frozen Pirate (1887), inspired perhaps by the Arctic Crusoe, published in 1854.

Barrie often set his plays on islands (The Admirable Crichton is a prime example), and he once remarked, in a public lecture: “I should feel as if I had left off my clothing, if I were to write without an island” (Birkin 253).

22. coral reefs and rakish-looking craft. Barrie’s Neverland is deeply literary, containing elements of adventure stories (islands, pirates, reefs, and boats) and also features of fairy tales (mermaids and fairy dust), along with streaks of poetry (the “caves through which a river runs” recall Coleridge’s sacred river that winds through caverns in “Kubla Khan”). The strange mix of pirates and fairies had been kept separate in two earlier works, The Boy Castaways of Black Lake Island and The Little White Bird, but was preserved in Peter and Wendy. Stories about pirates satisfied the desires of the older Llewelyn Davies boys, while tales about fairies appealed to the younger boys.

23. getting into braces. In contrast to its American usage as an orthodontic appliance, braces is the British term for suspenders.

24. coracles. Made of waterproof material stretched over a wicker or wood frame, coracles are lightweight, oval-shaped boats generally built to carry one person for the purpose of fishing or transportation.

25. We too have been there. The narrator reminds us here of his adult status and how, as an adult, he can no longer see or inhabit Neverland. His sole means of access is through sound.

26. Neverland is the snuggest and most compact. Fictional islands each have their own unique symbolic geography, but, as places cut off from the rest of the world, they all provide a site for reflecting on identity or reinventing the self. “To be born is to be wrecked on an island,” Barrie wrote, in the introduction to a 1913 edition of The Coral Island, a novel for boys first published in 1853 by the Scotsman R. M. Ballantyne. Barrie had reveled in Ballantyne’s work, which featured three boys—Ralph Rover, Jack Martin, and Peterkin Gay—shipwrecked on an uninhabited Polynesian island, where they encounter danger in the form of pirates as well as of natives who practice infanticide and cannibalism. Ballantyne, Barrie wrote, was “another one of my gods, and I wrote long afterwards an introduction . . . in which I stoutly held that men and women should marry young so as to have many children who could read ‘The Coral Island’ ” (The Greenwood Hat, 81). Coral Island inspired not only Barrie but also Nobel laureate William Golding, who read the volume as a boy long before he wrote the novel Lord of the Flies.

27. played on his pipes to her. Peter’s pipes enable him to imitate his earlier incarnation as a bird. “Being partly human,” we are told, he needs an instrument and therefore makes a pipe of reeds. In Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, Peter’s heart is “so glad” that he wants to sing all day long. He fashions a pipe of reeds and sits by the shore, “practicing the sough of the wind and the ripple of the water, and catching handfuls of the shine of the moon, and he put them all in his pipe and played them so beautifully that even the birds were deceived” (46–47).

28. sat down tranquilly by the fire to sew. Sewing and mending are feminine activities associated with Mrs. Darling, Wendy, and Tinker Bell. Tinker Bell is so named “because she mends pots and kettles,” and both Mrs. Darling and Wendy are seen sewing and darning. Smee, the most effeminate of the pirates, is seen “hemming placidly” before battle. Sewing and mending are linked to “tidying up” and the many other maternal efforts to create domestic order where there is anarchy, clutter, and disrepair. Associated with tranquillity, inwardness, and coziness, these activities stand in opposition to the world of adventure. Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Princess” set forth clearly the nineteenth-century gendered division of labor that is enacted in Peter Pan:

Man for the Field and

Woman for the Hearth:

Man for the Sword and

for the Needle She:

Man with the Head and

Woman with the Heart:

Man to command

and Woman to obey;

All else confusion . . .

29. the nursery dimly lit. In autobiographical reminiscences, Barrie remarked on the contrast between people raised in a nursery and those from other social classes who were not. He himself had never had a nursery, nor had the “most genteel friend of his childhood ever had a nursery.” “It seems to me,” he added (referring to himself in the third person), “looking back, that he was riotously happy without nurseries, without even a nana (but with someone better) to kiss the place when he bumped. The children of six he had met were, if boys, helping their father to pit the potatoes, and, if girls, they were nurses (without knowing the word) to some one smaller than themselves. He came of parents who could not afford nurseries, but who could by dint of struggle

send their daughters to boarding-schools and their sons to universities” (The Greenwood Hat, 151). Barrie’s parents valued education above all else and were willing to live modestly to ensure that their children attended the best schools. That education enabled Barrie to move with ease across class boundaries soon after his first success as an author. Upper-class friends and acquaintances invariably referred to Barrie’s short stature, his ubiquitous pipe, and his melancholy disposition, only rarely taking note of his humble social origins. The combination of genius, fame, and eccentricity did much to transcend class differences.

30. clad in skeleton leaves and the juices that ooze out of trees. Surprisingly, Peter Pan is not clad in greenery. That he wears a costume of delicate skeleton leaves points to his ethereal, “uncivilized” qualities as well as to a connection with seasonal change and death. Skeleton leaves can be produced by separating the cellular matter filling up spaces between a leaf’s veins or vascular tissue. The process is accomplished by dropping leaves in water and letting them remain in it until the fleshy matter decomposes but before the fibers begin to decay. Peter has presumably gathered skeleton leaves from the floor of the forest. Whatever their color may be, his way of dressing links him to the Green Man of Nature, a sinister figure connected with the devil. The oozing juices that hold the leaves together weld vitality to the hint of death in “skeleton” leaves.

CHAPTER 2

Peter Pan

Peter Pan Peter and Wendy

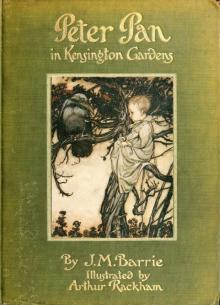

Peter and Wendy Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens Tommy and Grizel

Tommy and Grizel Sentimental Tommy

Sentimental Tommy When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life

When a Man's Single: A Tale of Literary Life The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens

The Little White Bird; Or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens The Little Minister

The Little Minister Peter Pan (peter pan)

Peter Pan (peter pan) Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Peter Pan (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)

The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) (The Annotated Books)